Hungary’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs Géza Jeszenszky talks about Pope Francis’ Budapest visit, the alleged Christian and conservative nature of the Viktor Orbán-led government and the prime minister’s position in the European Union. He also explains the “strange” character of the opposition coalition, and why he would be “pessimistic” if Klára Dobrev became the joint opposition PM candidate after the upcoming primaries.

Host: Zoltán Kész

Initial reports on Pope Francis refusing to meet Hungarian political leaders turned out to be wrong. Besides celebrating the closing mass of the 52nd International Eucharistic Congress in Budapest tomorrow, the Pontiff will have a short meeting with both the country’s president János Áder and prime minister Viktor Orbán.

Géza Jeszenszky, a descendent of Lutheran ministers, welcomes the Pope’s visit to Hungary and recalls his personal encounter with a former head of the Catholic Church, Pope John Paul II, during his visit to Hungary in August 1991. Mr Jeszenszky describes Pope Francis as a “very original, courageous and controversial man”.

In comparison with Slovakia, where the Catholic leader will spend three days of his Central European trip, the papal visit to Hungary will be short. Nevertheless, the former politician doesn’t consider the semi-official visit a “diplomatic defeat”.

“Slovakia is a more devotedly Catholic country and its leaders are practicing Catholics. Slovakian bishops do have a strong presence in the Vatican, where there is no Hungarian Catholic representative, except Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See,” Mr Jeszenszky told CEA.

Most likely, Hungary’s stance and attitude on immigration and human rights didn’t help the country’s leaders when seeking a longer papal visit. Other factors, just like the “unacceptable language” used by some of the government’s main supporters, could also have played a role in the scheduling of the semi-official visit.

Christianity and Fidesz

Mr Jeszenkszy has some serious doubts about the ruling party’s propagated Christian and conservative nature. He recalls the current ruling party’s anti-clerical past and recalls the visit of John Paul II, which wasn’t received neither by Viktor Orbán nor his Fidesz party in “polite or warm terms”. “They were ridiculing it.”

In the first freely elected parliament after the political transition, Fidesz party members were openly criticizing other MPs for their faith and Christianity.

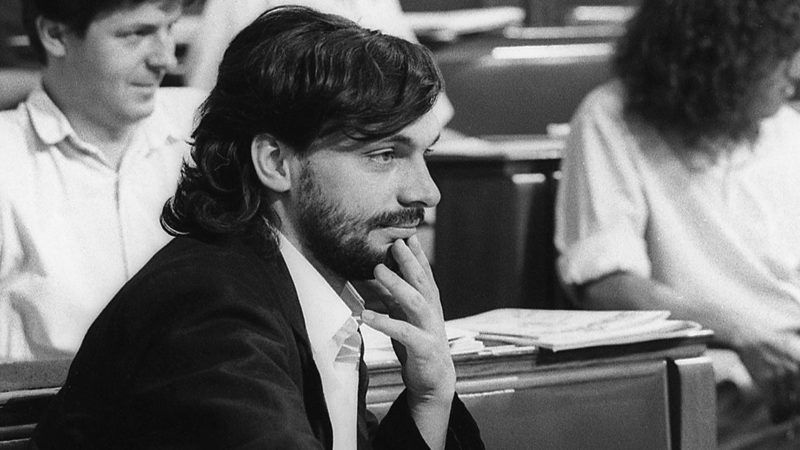

Photo credit: Zoltán Szalay, Fortepan

“I accept that there are true conversions, we know cases from the Bible, but I suspect from many of the policies of the current government that this conversion is not really authentic. Many of the policies are not expected from a true Christian believer.”

Conservatism and Orbán

Due to the same government’s policies, the diplomat, who considers himself a liberal conservative, casts doubt on the prime minister’s alleged conservative views. Fidesz leaving the EPP Group and wanting to create a new grouping of radical right parties, point in the same direction. “Orbán has nothing to do with conservatism,” he claimed.

In his view, Hungary’s head of government is more inclined to the politics of Marine Le Pen, Giorgia Meloni and Matteo Salvini. In Germany, in order to preserve the support of Chancellor Angela Merkel, Orbán didn’t dare to openly endorse the AfD.

“He and many of his colleagues almost openly say things that these radical rightist people say in Germany.”

Opposition on one platform

Talking about the upcoming Hungarian parliamentary election, he is unsure how far Fidesz will be ready to go to preserve its majority. Due to amendments of the electoral law in recent years, the ruling party faces a broad spectrum of political forces stepping up as one major opposition coalition.

“This is a rather strange kind of alliance. It was imposed upon the Hungarian political establishment by Fidesz.”

Photo credit: Zoltán Máthé, MTI

The goal of the ruling party’s strategy was to put all critical voices of the current administration onto the same platform. “This way the government is to suggest that that the opposition is practically identical with Ferenc Gyurcsány.”

Despite the surge of Klára Dobrev, Mr Gyurcsány’s wife, as a possible joint opposition PM candidate in polls, many voters, including Mr Jeszenszky, question whether the government critics can win the parliamentary election with a PM candidate from the Democratic Coalition (DK).

“For many people, including myself, Mr Gyurcsány and his wife are not very attractive as political leaders. His party is damaging the chances of the opposition to win,” he said.

“The making of Ms Dobrev to be the common candidate of the opposition seems to give the best chance for Fidesz to win the next election,” the diplomat added.

What if it’s Ms Dobrev?

With the opposition primaries about to kick off on 18 September, a lot is at stake for the political parties competing against each other. It will be the first time that six parties of the opposition join forces to try to counterbalance the power of the ruling party in the election.

A victory for Klára Dobrev in the primaries would cause an unusual headache for many conservative and centrist voters. However, Mr Jeszenszky acknowledges Ms Dobrev’s intelligence and merits, her party couldn’t win his confidence. A particular concern for the former Foreign Minister is the equal voting rights for Hungarians beyond the country’s border. “I am strongly committed to the right of the Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin, the victims of the Trianon Treaty and their rights.”

Photo credit: Tibor Illyés, MTI

“Technically, she may be capable as a politician, but politically she is really unacceptable for many Hungarians. I would be very pessimistic [if she became the PM candidate]. It would be very hard for me to vote for her.”

Jobbik and the shift towards the center

The politically colorful nature of the opposition coalition generates debate and some reservations. Besides DK, the active role of Jobbik, a former far-right party, in the coalition is a thorn in some other voter’s eyes. “I think the problem with Jobbik is rather its past.”

The diplomat qualifies Jobbik’s move towards the center as “understandable”. Péter Jakab, the party leader, realized that the group’s only chance to be in a government, is to take in more centrist positions.

“They certainly discarded many of their unacceptable and detestable policies. How genuinely? Well, again. I cannot read the mind of Mr Orbán. Neither of Mr Jakab.”

Jobbik’s current political platform is “certainly less rightist” than many of the policies and pronouncements of Viktor Orbán, his party and his followers.

Cover photo credit: Pope Francis celebrating a mass in the St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican on 6 June 2021.

Giuseppe Lami, Pool, Reuters

Géza Jeszenszky is a Hungarian historian, politician, academic, diplomat, and Hungary’s former Minister of Foreign Affairs (1990-1994). He was ambassador to the United States (1998-2002), later to Norway and Iceland (2011-2014). Together with Prime Minister József Antall, he was one of the founders of Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), a former center-right party that won the first parliamentary elections in Hungary in 1990.

Photo credit: MTI