The fate of Polish Jewry seemed grim following the German Nazi invasion and systematic killing of a once-thriving community that lasted hundreds of years in the country. Now, Jewish groups within cities like in Lublin are not just fostering education programs about the religion, but revitalizing it in spectacularly compelling ways.

Author: Jared Feldschreiber

Leading up to near the start of the Second World War, Lublin, Poland was a thriving place for Jews. In fact, before the war, approximately 40,000 Jews lived there as the city had been seen as Europe’s epicenter for all forms of Jewish life — be it in culture, business, and religious scholarship. Lublin had also been the hub for the Hasidic movement – a method to create a Jewish way of life that emphasized growing closer to God and the Torah.

By the 19th century, while anti-Semitism loomed large in different pockets of the globe, the city’s Jewish inhabitants were allowed to live within their districts and permitted to buy land for civil purposes. Yet throughout the century, its commerce and industry still expanded as Jewish owners bought hospitals and schools. In 1897, the first Hebrew school was built as its population reached close to 24,000.

Even after World War I, Jews continued to thrive in Lublin. Many institutions devoted to politics, education, theatre, and sports were set up by Jewish organizations, and several printing houses also produced works in Hebrew. The Jewish Rabbinical Academy opened in June 1930 even though its founder Rabbi Meir Shapiro passed away in Oct. 1933. All the books in the library were later confiscated by the Germans during the Nazi occupation, and its equipment was either stolen or destroyed.

Today, this historical building that was Rabbi Shapiro’s brainchild has been renovated as Hotel Ilan; a treasure trove for Polish Jewish history; not to mention a spacious building for continued Talmudic study and lodging.

Photo credit: Jared Feldschreiber

“The idea behind the building was very unique,” says Agnieszka Litman who serves as the Lublin Branch Coordinator at Hotel Ilan. “[Rabbi Shapiro] realized that you not only needed a place to learn for the students where they can study Torah, but you also needed to create a space for them to have a comfortable life, so they can learn more and more. When he was designing this building, he made sure there was space for prayers, for eating together, and bedrooms so the students could live here.”

In the 1920s, Rabbi Shapiro became the first Orthodox Jew to serve in Poland’s Parliament. His death, however, served as a sad and ominous harbinger for the fate of Jews living in Lublin and European Jewry at large.

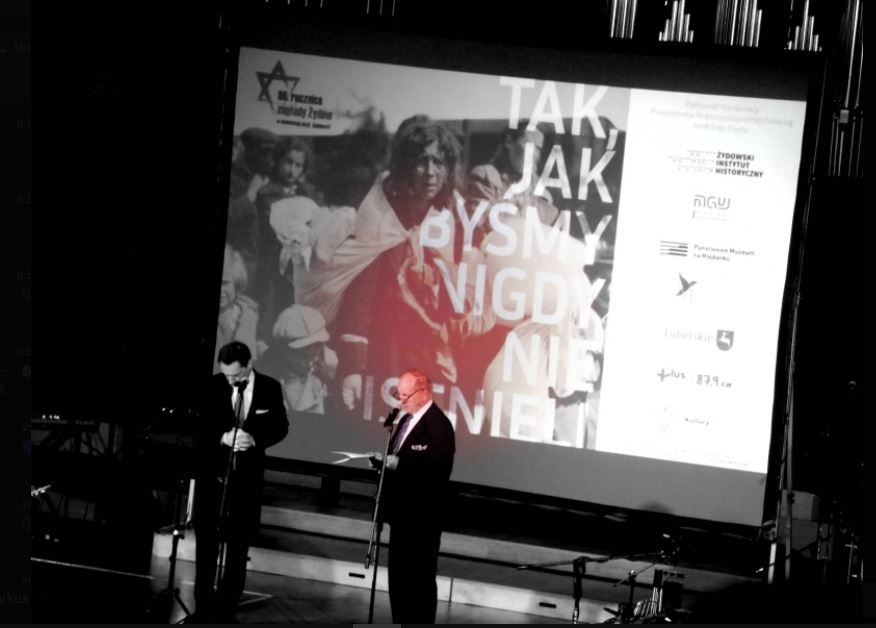

After the Germans captured Lublin on Sept. 18, 1939, the city became a center of mass extermination of Jews during the Holocaust. Much of these atrocities occurred in the Majdanek death camp. Initially a site of a labor camp, Majdanek was transformed into a death camp by the Nazis, and mass transports of Jews began arriving there beginning in April 1942. Action Reinhard, a secret plan devised by the Germans to exterminate Jewish Poles and plunder their assets, was also implemented in the same month. On April 27, 2022, a commemoration to honor Lublin’s Jews that were so heinously killed by the Nazis took place at the Filharmonia Lubelska near the city’s university. The poignant event featured a 58-minute documentary on Action Reinhard as well as guest speakers, and a rock concert designed mostly for high school students.

“I think the most important thing for me is [seeing] the young people [here]. [They need] to understand what happened because this is the knowledge that [approximately] one million eight hundred Polish citizens of Jewish origins perished,” says Albert Stankowski, the head of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum, and the former Head of the Digital Collection Department of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews. “It was the biggest massacre on Polish land, and this is a fact that is not so well known.”

Photo credit: Jared Feldschreiber

Schutzstaffel (SS) and police forces liquidated the ghettos and deported Jews by rail to these killing centers. Most were sent from ghettos set up throughout Europe. According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Nazi Germany and its allies established more than 44,000 camps and other incarceration sites between 1933 and 1945.

“The most important aspect is the effect of what had happened here – the perishing of Jewish communities,” continues Stankowski. “These were generations who were living here; for five, six, seven, and eight hundred years, and suddenly, this became empty. Today, we don’t have more than 20,000 Jews all over Poland compared to 3.5 million before the war.”

Stankowski also explains that the mammoth hardcover books entitled As If We Had Never Existed, which were published by the Warsaw Ghetto Museum that is set to open in 2025, and which were distributed after the event ended, provide the blueprint for better understanding. “These books will be in libraries throughout [Polish] towns and schools. This is important. The Jewish Historical Institute – located in Warsaw — has a huge collection of diaries of those who survived, mostly during the time of the Soviet Union. They wrote what had happened, and documentaries made by Claude Lanzmann had recordings of the witnesses. Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation [also] did an amazing job [with testimonies from Holocaust survivors].”

Rabbi Symcha Keller, who is head of the Jewish community of Łódź – another Polish city that once had a thriving Jewish community – and who also participated in the music set of the commemoration, remains steadfast in glorifying Jewish teachings and culture within his native land. “I make music in the Jewish-Hasidic style. I live in Lublin, and I am here to spend some time with my friends. But for all the big holidays, I am the chazzan.” A chazzan is a person who leads the synagogue services.

Photo credit: Jared Feldschreiber

Lublin is truly a beautiful city that had its Jewish history decimated by German Nazis. While there remains a struggle to restore this once mighty heritage, Agnieszka Litman conveys an optimistic beat. She underscores that it will happen mainly since residents are eager to see it. “We want to remember the past but also build for the future,” says Litman. “People here are open to it. I think it’s now a great time to start working on the presence of the Jewish community in Lublin every day – in education and culture. It’s important to be present and be seen and to educate people that this is the community that exists.

These Jewish organizations, which work in Lublin, are where you can learn and ask questions,” insists Litman.

Cover photo credit: Jared Feldschreiber

Jared Feldschreiber is a freelance reporter and contributor to Central European Affairs Magazine. He is based in Warsaw, Poland, and often chronicles literary figures, filmmakers, and dissidents in nascent democracies. Reckless Abandon, his novella, is available worldwide.

Twitter: @jmfeldschreiber

Photo credit: Ilan Sherman