Former US Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Daniel Fried explains how Belarusian “air piracy” means more than a simple hijacking and why democracies should believe in their values. He also talks about sanctions “not working until they do”, the long arm of authoritarian leaders reaching beyond their own borders, and why Viktor Orbán is “no fool”.

Host: Balázs Csekő

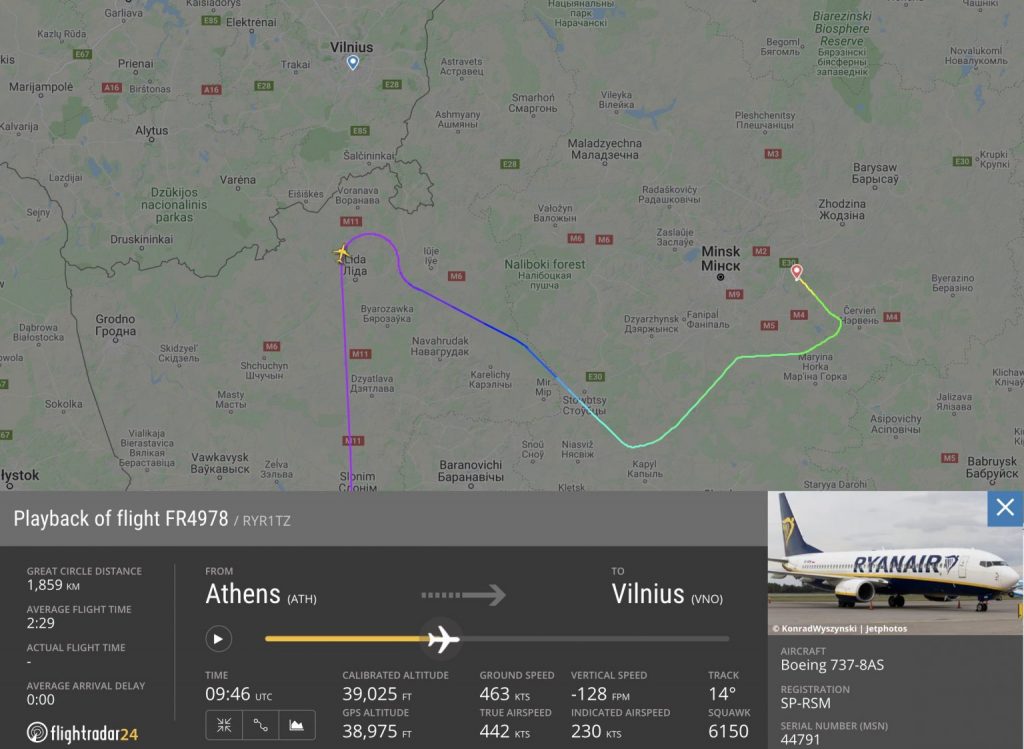

Few people thought the trajectory of the Athens-Vilnius Ryanair flight 4978 would go down in the history books when it took off at 10:28 from Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport on 23 May 2021. Two hours later, as the aircraft entered Belarusian airspace, the pilot of the plane was informed of a “potential security threat on board” passed on by local air traffic control. Immediately afterwards, a MiG-29 fighter jet of the Belarusian Air Force was sent to escort the flight to Minsk, where it landed at 1:16 p.m. Already on the ground, dissident journalist Roman Protasevich and his girlfriend were detained.

“This is active air piracy,” Daniel Fried, who became one of the US government’s foremost experts on Central and Eastern Europe and Russia, told CEA Magazine. The former diplomat, who spent four decades working for different US administrations and witnessed firsthand the fall of the Soviet Union, can’t recall a comparable incident, where a government forced down a plane to grab a dissident.

Larger than hijacking

For many, it could seem, that the conflict is purely about the hijacking of a commercial flight. “Larger issues are at stake in addition,” Mr Fried claimed.

The rogue behavior of Belarus is “an assault on European airspace, the European Union, democracy, and the rules-based international order.” A malign conduct of this magnitude requires appropriate response. Few understand this better than the US diplomat, who in his role as State Department Sanctions Coordinator, negotiated with Europe about punitive measures after Russia’s 2014 invasion of Eastern Ukraine. “We are right back at this kind of issues”.

Within twenty-four hours, the EU heads of state and government, called on EU carriers to avoid Belarusian airspace and agreed to ban overflight of EU airspace by Belarusian airlines and prevent access to EU airports. The unusually rapid move European leaders point to real commitment in the issue. The decision was not taken lightly, but the EU responded “with speed and strength.”

Sanctions don’t work until they do

Critics are less convinced by the approved EU sanctions and highlight these could hurt the Belarusian people more than President Alexander Lukashenko himself. Still, Mr Fried thinks the “right steps” were taken. Aviation sanctions could in fact have a negative impact on citizens, but for them, Lithuania’s capital Vilnius remains within reach both by car and train. Should Mr Lukashenko pull out a more restrictive card by ordering the shutting down of his country’s borders and starting to act as a traditional Soviet leader, it could easily be met with discontent by Belarusian society.

Sanctions without downside risks are impossible. Although, policy makers try to follow the “no risk, all gain, no pain” principle, they seldom exist. Mr Fried, a sanctions expert, would not let the wealth of corrupt authoritarians untouched. “I don’t know where Lukashenko keeps his money, but it would be nice to do something about that.”

More sanctions will follow. At this stage of the events, individual ones against the president of Belarus and his inner circle are highly likely. Sanctions against the country’s companies and the blocking of Belarusian sales of government bonds are necessary.

“There is no reason we should allow the regime to borrow money using our system when they are also showing contempt for another piece of our system which is the civil aviation agreement.”

History shows impact of sanctions can grow over time. Sanctions imposed by the West over the Soviet Union in 1980s were originally met with skepticism. “They didn’t work, until they did. It turned out that they had an accumulative effect on hollowing out the Communist system,” Mr Fried explained.

For this reason, the former US Ambassador to Poland, advocates for a mixture of patience and belief. Similar to the 1980s, when Soviet citizens understood that socialism didn’t work and what later resulted in the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

“We shouldn’t discount the possibility that pressure sustained overtime and support for democratic dissidents can have effects we don’t see in advance. We should believe in ourselves and our values.”

Do sanctions matter?

Punitive measures are part of international relations. To what extent they can be effective, remains a topic of dispute. Sanctions against Cuba, Venezuela, North Korea, Iran or Russia show that they do not necessarily have an immediate impact. “They can work, but don’t be greedy or impatient.”

In a similar situation, sanctions on Iran from the Obama administration made the Mullah regime sit down to the negotiating table which ultimately led to the Iran nuclear deal. Later, the Trump administration pulled out of the JCPOA and presented a 12-step plan . “They were greedy. No way sanctions were going to convince Iranians to change all aspects of their behavior.”

Governments can unequivocally take steps at the margins as a consequence of sanctions. They can sometimes produce “unexpectedly large results, but very seldom according to your preferred time table.” Just as a rule of policy making says: “We often overestimate what we can achieve in the short run, but underestimate what we can achieve in the long run.”

The long arm of authoritarians

The case of Roman Protasevich reveals another specific nature of authoritarian regimes, namely that they do not stop at their borders. For them, the persecution of dissidents abroad is a common practice. The poisoning of a former Russian spy and his daughter on a bench in Salisbury, UK in 2018 is an example of such modus operandi. But how should democracies and open societies react to this type of behavior?

“Start keeping an eye on Russian intelligence agents,” Mr Fried said. “Be vigilant. Identify them. Put a spotlight on them. If they act, retaliate.” Aggression should have consequences.

Intimidating dissidents is also on the agenda of Mr. Lukashenko. “Tyranny in one country doesn’t necessarily stay inside that country. It can affect us all,” Mr Fried argued. “Lukashenko, like Putin, wants to make a point that no dissident is safe anywhere in the world,” he stated.

No proofs “so far” indicate Russia would be involved in the Ryanair flight incident over Belarus, but as we speak, the first information about Russia denying landing rights to Austrian Airlines and Air France machines is pouring in. The reason: Both airlines were respecting the EU decision and didn’t fly over Belarus airspace on their way to Moscow. The decision, however, only affects traditional flight routes going over Belarus. The conflict between Belarus and the EU is seemingly expanding to Russia.

Pro-Kremlin voices within the EU

Pro-Russia rhetoric doesn’t sound unfamiliar within the EU either. The former American diplomat, however, is not convinced of those voices “doing a great job”. Czech President Miloš Zeman, “one of the EU’s most Kremlin-friendly leaders”, was slammed for his comments on the findings on the Vrbetice explosions by the Czech Security Intelligence Service (BIS) and the National Center for Combating Organized Crime (NCOZ).

“The Czechs started to sound like Poles and Lithuanians about Russia,” Mr Fried said.

Photo credit: AFP

Hungary, after blocking EU criticism of China on Hong Kong and a statement on the Israel-Palestine ceasefire, did not oppose an EU consensus on Belarus. As a political practitioner, Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán needs the support of the Polish government that represents a clear pro-democracy position on Belarus.

Would Hungary’s head of government put his alliance with Warsaw at risk? Definitely not. “Viktor Orbán is many things, but he is no fool. He is a smart guy and a capable tactician.”

Could Orbán’s position on Russia change in the future? Mr Fried thinks so. “Right now the Czechs are strong on Russia, the Slovaks and the Poles are pretty good. If European opinion starts to move in the direction of a stronger Russia policy, Hungary will not fight that.”

Greece, another EU country with a “more Russia-friendly government”, was hung out to dry once again. Not enough that Russia was caught trying to sabotage Greece’s Prespa Agreement with North Macedonia, “now they have messed around the flight from Athens to another EU capital”.

Poland and Lithuania as examples

Actors who think that aggression from authoritarians in Europe has nothing to do with them should think over their position. The governments of Poland and Lithuania have showed understanding this phenomenon better than many others.

On the international stage, lessons could be learnt from both countries for their attitude towards Minsk. The two countries did “a magnificent job” in supporting the Belarusian democratic movement.

“Should Russia start leaning on Lithuania for its position on Belarus, the solidarity ought to enjoy not just words, but deeds ,” the retired diplomat concluded with a reference to NATO.

Cover photo credit: Sergei Gapon, AFP

Amb. Daniel Fried is an American diplomat, who served as Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs from 2005 to 2009, as US Ambassador to Poland from 1997 to 2000, as a Special Envoy to facilitate the closing of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, and as a Coordinator for US embargoes. He also served as a Special Assistant to presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. He is currently a Distinguished Fellow at the Atlantic Council. Twitter: @AmbDanFried

Photo credit: Atlantic Council