Political scientist Thorsten Benner speaks about the EU-China investment deal, why EU-Chinese relations will have a discontinuation after the September election in Germany, how Aleksandar Vučić is used as a propaganda tool by Beijing and why hosting Fudan University in Budapest is one of the latest attacks by Viktor Orbán on academic freedom and democracy.

Host: Balázs Csekő

After 7 years of negotiations, the European Union and China agreed upon an investment deal at the end of last year. The reactions to the agreement were mixed. Some showed support to the deal, but critics didn’t hesitate long to highlight the weak points of the accord.

Thorsten Benner, the director of GPPI, says there are two ways to look at the agreement. In terms of the added benefits for European economic actors, the results are “very modest”. The agreement is “extremely soft” on labor rights and contents itself with declaration on the Chinese part to make some efforts to adhere to International Labor Organization standards on forced labor. However, with a non-existent enforcement mechanism, the Chinese commitment remains in dispute. “As we have seen with Hong Kong, Beijing doesn’t really adhere to international treaties if it thinks it hurts its national interests,” he said.

The overall political context is even more problematic. Angela Merkel, the primary champion behind the deal, assisted by French President Emmanuel Macron and EU Commission negotiators, rushed to the finish line just as the Biden Administration was preparing to take office in Washington D.C.

A slap in the face for one party is a “big boost” for the other side. Chinese President Xi Jinping achieved Beijing’s primary goal to block a united front between Brussels and Washington on China. “The Europeans handed the Chinese government a diplomatic victory on a silver platter”, Mr Benner explained.

Photo credit: Screenshot/EPC

Rushing to the end of 7 years of negotiations could have its consequences. In order to ratify the investment deal, the European Parliament should give the green light. After the first wave of European “Magnitsky sanctions” on China, the government led by Xi Jinping decided to impose counter sanctions on MEPs, think tanks and researchers. “All this makes it highly unlikely for the European Parliament to agree to this agreement.”

Merkel and China

Despite critical voices, Angela Merkel’s approach has been mainstream within Europe for a longer period, but her position has come under fire recently. Europeans who think there is a competition of systems with Beijing have become more vocal.

The German Chancellor’s approach is to pursue economic and political relations with Beijing rather than to forego the opportunity the Chinese market represents for German and European companies. “She thinks that we cannot afford not to be present in China.”

Merkel also believes there is a hedging deal that Europe needs to achieve. In her view, President Trump was not just a “fluke”, and the future political trajectory of the US remains insecure. In case Washington becomes a more nationalistic geo-economics actor and starts slapping sanctions on the EU, “it’s good to have a hedge and not to be all alone.”

She already gave up the hopes that intensifying economic ties could lead to the opening up of the Chinese political system. For all this, Merkel doesn’t support the idea of a containment policy, as it would make Beijing to be more aggressive, but prefers the pursuit of a middle path of conditional engagement. In her view of history, China is coming back to its natural place as a key world power after an interlude of 200 years.

The Merkelian China approach has supporters across Europe. Spain’s prime minister Pedro Sánchez, French president Emmanuel Macron, Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić are some of the most notable followers of the German Chancellor’s China line.

German elections as shake-up

With German parliamentary elections taking place later this year, Merkel’s China policy is most probably having its last days. “You will not see a continuation of the Merkel approach in the Chancellor’s office”, Mr Benner said.

The Greens, likely to have a strong presence in parliament after the vote in September, are expected to make their weight felt in terms of government policy. They are critical of Merkel’s approach, but there are also contrary opinions within her own party, the CDU. Norbert Röttgen, the chairman of the foreign affairs committee in the Bundestag, leads the inner-party critics. His concerns are echoed by the SPD, which sees China as a systemic rival, and the liberal FDP.

Beijing’s most vocal supporters are in the Left Party and within the Chancellor’s CDU. Pro-China voices and enablers of Merkel’s policy are all over the German political scene: PR groups, spin doctors and lobbyists hired by Beijing and their companies are part of the big picture. Volkswagen, one of Germany’s leading motor vehicle manufacturers, eyes the Chinese market as a key part of its future business. Those expecting a “full shift” after the September election, could be disappointed. “Investing more to be more competitive in this competition of systems with Beijing is what you will probably see from the next government,” the political scientist argued.

EU’s ‘Magnitsky Act’

Last December, the European Union formally adopted a regulation establishing an individual sanction regime for grave human rights violations. The EU’s sanction mechanism, unofficially dubbed as the ‘Magnitsky Act’, was activated against China for the first time in March 2021, when the EU announced targeted sanctions against four people and one entity accused of perpetrating human rights violations against Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, a northwestern region of China.

Photo credit: Journeyman Pictures, Google Maps

Whether it’s an effective mechanism vis-a-vis Beijing’s aggression and repression on the human rights front, is an open question. This type of sanctions usually works if they are being slapped on a small power by a larger power without the likelihood of retaliation. The Chinese leadership decided to retaliate disproportionately and sanction not just elected officials within the EU, but think tanks and researchers like German anthropologist Adrian Zenz. “I’m not sure that these sanctions are the right way to go,” Mr Benner warned.

“It could be more effective if Europe signaled its determination to reduce economic dependence on the Chinese market. This would really cut to the core of relationship rather than continuing on the sanction path,” he added.

Imposing sanctions will have little improvement on the situation on the ground. Europeans should focus on making sure that none of the companies based in the EU are complicit in human rights violations that are being committed by the Chinese Communist Party. “The right reaction is not to do more individual sanctions, but letting Beijing know we will not be bullied.”

CEE and China

There is a temptation within Germany that Central and Eastern European countries represent prime problems in EU-China relationships, but Germany’s political and economic dominance within the EU cannot be overseen. By taking these factors into consideration, the “weakest link” in Europe on China is German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Mr Benner also criticizes both Viktor Orbán and Aleksandar Vučić for their China course, but underscores the necessity of targeted and measured criticism. He doesn’t blame the two leaders for relying on Chinese vaccines amid the Covid-19 crisis. “If they are effective, that’s a good thing for both the Serbian and Hungarian populations.”

However, it is important for these governments not to make themselves a “handy tool” of Beijing’s propaganda efforts when receiving China-made vaccines or medical goods. Blaming the Serbian leadership for turning to Beijing to get critical medical goods would be a “mistake”, as there were moments when the EU was unable to supply those goods to Serbia.

“We can criticize if the Serbian government makes itself a tool of Chinese propaganda and also consciously undersells the economic ties and support that Serbia receives from the EU.”

Despite the real figures, an opinion poll by BCSP showed that most of the Serbs believe China (75%) helped their country the most during the Covid-19 crisis, with the EU scoring only 3%. “This is a striking example of how necessary clarity, transparency and communication by the national governments and the European Union are.”

Fudan and Orbán

Hungary’s search for economic alternatives for the one-dimensional dependence on German companies for the country’s economy cannot be criticized. However, the lack of tangible economic benefits in return of the trade and investment promised of Viktor Orbán’s opening up to the East, in particular to China, haven’t materialized yet.

Mr Benner rebukes Hungary’s prime minister for having an authoritarian like-minded alliance with Beijing. “It seems that he tries to use his closer ties to China as a leverage against the rest of the EU and Brussels.”

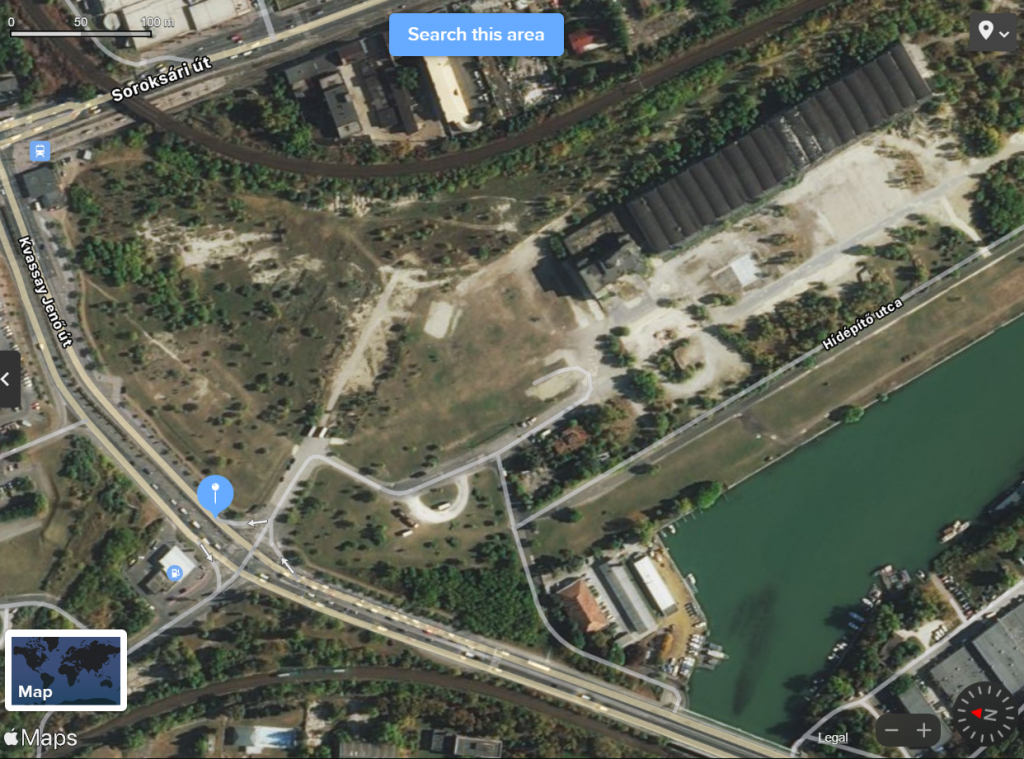

Despite calling Brussels “the new Moscow”, the Hungarian leader has never taken a swipe at Beijing’s hegemonic aspirations in the Central and Eastern European region. This adds up to the chasing away of the Central European University from Budapest, a promoter of open society, and rolling out the red carpet to the Shanghai-based Fudan University.

Photo credit: Apple Maps

Viktor Orbán’s decision to invite Fudan University, one of the top Chinese academic institutions, to Hungary shows that he sees China as part of the future. With Chinese academia “on the top” and currently fanning out, he saw an opportunity to be one of the first European bridgeheads of this evolution. “Orbán is sending a symbolic signal that fits with his overall agenda on academic relations and the way he would like universities to be run,” Mr Benner said.

For the Hungarian leader, well-known for curtailing civil liberties in his country, tight political control over academia is an attractive proposition. “Fudan is a huge symbolic blow to academic freedom and everything academia stands for in an open society and democracy.”

Critics also emphasize the increasing security risk that the elite university could pose to Hungary and the European Union. Fudan is well-known for collaborating with the Chinese intelligence services and running its own spy school. In spite of security concerns, the “biggest danger” of the campus lies elsewhere.

“More problematic is the disregard for academic freedom and key principles of democracy, embodied by the dual decision involving CEU and Fudan.”

Cover photo credit: Original photo: Johanna Geron, EPA-EFE

Thorsten Benner is a political scientist, the co-founder and director of the Berlin-based Global Public Policy Institute. His areas of interest include the United Nations, security issues, data and technology politics and the interplay of Western and non-Western powers in the making of a global (dis)order.

Photo credit: GPPI.net