The Central European Affairs Magazine has spoken to several figures in the vibrant Polish cinema world in order to get a better feel of how coronavirus has been hitting the film trade, and to learn of what they see as hopeful trends moving forward.

Author: Jared Feldschreiber

In November 2020, Variety, America’s top film trade magazine, headlined its story, ‘Prolific Polish Industry Keeps Camera Rolling Amid Pandemic Woes,’ chronicling how the many challenges the COVID-19 pandemic affected the country’s film industry. In recent months, this very industry has indeed deftly and effectively adapted to these changes.

The pandemic has taken a heavy toll on Europe’s sixth-largest theatrical market, which broke records in 2019 for total box office and admissions. With the government’s decree on Feb. 12 that cultural activities, including cinemas and theatres were reopened at 50% capacity, for film buffs in the country, it’s a welcoming opportunity – even as fear, uncertainty, and angst still remain for the public – and for the film industry.

Film New Europe, a networking body that delivers free online newswire for film institutions in Central-Eastern Europe and the Baltic region, reported that cinemas and theatres were only allowed to sell 25% of places available, making operations financially unviable to most cinema operators. In recent days, Mateusz Morawiecki, the country’s prime minister, said the move to reopen the cinemas had been taken since the disease stabilized in most areas. He also underscored, however, that the reopening would be ‘conditional’ as the situation will be routinely reassessed, according to the latest information on coronavirus infections and other parameters.

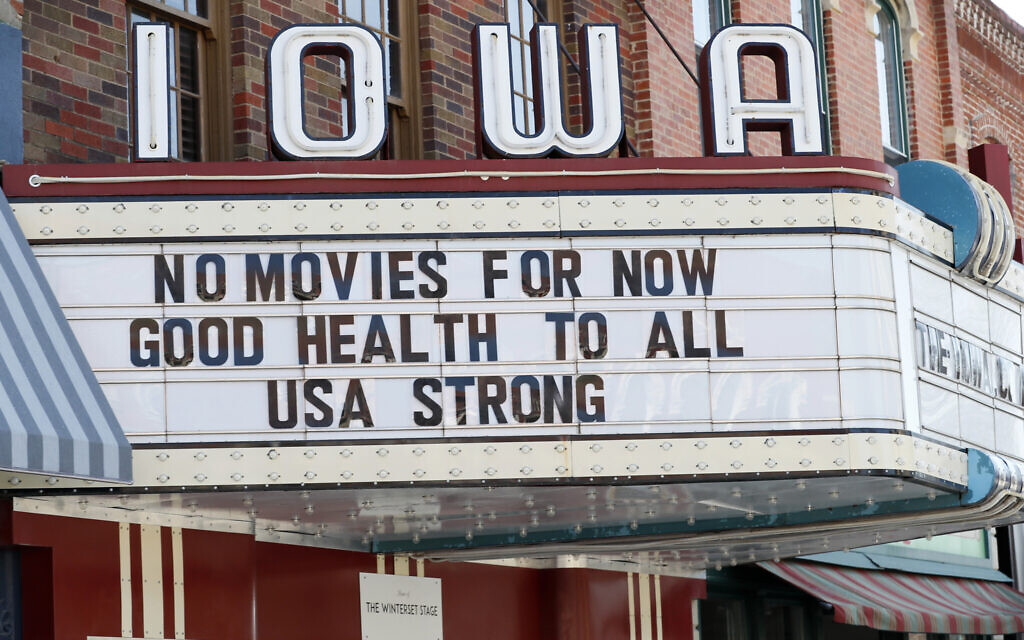

Photo credit – Grzegorz Michałowski, PAP

In June 2020, Robert Kijak, CEO of Next Film, told Variety that he estimated the three-month closure – at the time – resulted in a loss of 10-11 million ticket sales. This represented approximately 20% of the year’s projected total. During that period, Next Film canceled two of its local premieres because of COVID-19. Variety also reported that the big chain Multikino slashed prices across its venues.

Next Film, based in Warsaw, promotes and distributes mainly Polish films in cinemas and on DVD. The production and distribution company, established in 2012 as part of Helios Group, and a member of Agora S.A., Next Film is clearly one of the biggest media groups in Poland.

Central European Affairs: In the latter months of 2019, which films were still in production, and approximately how much have film crews been forced to spend for extraneous things, just to keep their sets “clean and safe?”

Robert Kijak: As far as our projects were concerned, none were in production during the winter months of 2019, early 2020, and into the spring. Our partners managed to wrap up production before the coronavirus emerged in Poland, and all restrictions were put in place.

Central European Affairs: Which films were Next Film set to distribute that had to be postponed, and would you care to comment on the overall net loss that had been caused as a result of this pandemic?

R.K.: In 2020, we were able to release four films – two in the beginning of the year and two in the autumn. Our January and February releases — ‘How I Became a Gangster: True Story’ and ‘365 Days’ — were the first and third most grossing titles of the year at our local box office. Autumn releases — ‘Triple Trouble’ and ‘Overclockers’ — were definitely affected by the pandemic, but it’s hard to estimate the exact numbers in sales. As of this moment, most of our upcoming titles do not have a set release date. ‘Dial W for Murder,’ ‘Bo we mnie jest seks’ (‘Because There’s Sex in Me’), which is about the Polish singing and acting icon Kalina Jędrusik, and ‘In-Laws,’ are among them.

Central European Affairs: When do you foresee these films resuming their production?

R.K.: Film production in Poland resumed in the summer of 2020, and it continues to work thanks to all safety restrictions.

Central European Affairs: Briefly describe how international sales were impacted overall by the pandemic.

R.K.: Our whole industry has suffered enormous loss. At the same time, it’s the only industry that can’t be launched back into normal functioning overnight. It depends not only on cinemas reopening, but also on the distributors and producers. ‘No Time to Die’ [ed.:The new James Bond film] is a perfect example of this.

Central European Affairs: With online film fests becoming the trend even before the pandemic, do you sense the entire paradigm has already shifted?

R.K.: Although online film fests were a great success, online events won’t be predominant in the future. We all dream of meeting face-to-face and discussing films that we can watch on the big screen. It doesn’t mean that all that the digital know-how professionals developed in these last several months will just dissolve once coronavirus fades away. Certainly it will be very useful for “hybrid festivals” in the future.

To examine the future of film festivals, its deep origins, and where Polish film’s future may lead, the Central European Affairs Magazine turns to Tomasz Kolankiewicz, the artistic director at the Polish Film Festival in Gdynia. Well-versed in world cinema, Kolankiewicz is a film programmer who has collaborated with some of the biggest artistic institutions in the country, including Nowy Teatr, Polish Filmoteque, and TVP Kultura — the first Polish cultural-themed channel.

Central European Affairs: How have you surveyed the current film market within the past 11 months as a film connoisseur, and your capacity as a film festival artistic director?

Tomasz Kolankiewicz: For obvious reasons, almost all of cinematic life has migrated online. Festivals, screenings, and premieres have taken place not in cinemas, but on Internet platforms. I took part in many online festivals and some industry venues, and meetings. I am used to online platforms on a daily basis so it was not that different for me. I was lucky to participate in some “normal” festivals during the summer. Definitely this past year was extreme in every sense.

Central European Affairs: What types of professional sacrifices have the industry been forced to make as a result of this pandemic? In addition, would you discuss the overall toll on the filmgoers’ experience of “live cinema,” as local cineplexes have had their revenue slashed?

T.K.: I think that we are observing a vast change in the entire production and distribution process. I think it has been happening for some time now and the COVID-19 situation has only sped things up. The biggest sacrifice was the closing of cinemas and stopping the production process. That was very hard not only for the film artists but a huge amount for the “below the line” workers, like caterers. I think that many small cinemas may not reopen if they are not sufficiently helped by the government, and by local authorities.

Central European Affairs: With online film fests becoming the trend even before the pandemic, do you sense the entire paradigm has already shifted?

T.K.: I don’t think so. I feel that the online medium will stick with us, but I still strongly believe that participating in a film festival is not only a question of watching films. The “festivalization” process will probably get even stronger since people need to be together after months of lockdown. To participate in cultural events together is one of the foundations of a modern democratic society. I believe it will continue but probably with different, online additions. I call these “hybrid” forms, which combine online with “normal” events.

Central European Affairs: What remains some of the main demands for individual players, like for film crews, actors, sales teams, agents, and film fest artistic directors, to keep the Polish film industry moving forward?

T.K.: I think it is crucial that we stick together, and to not forget about one another. The film industry – just like any other – is like a house. If you remove its bricks, it will fall down. So if small local cinemas collapse, the problem is not only for the owner and the members of staff, but eventually also for the major producers and star actors.

Central European Affairs: What do you make of the current crop of Polish film talent, and where do you think it’ll be on the world scene in 7-10 years?

T.K.: I think that the level of student films, debuts and second films by new directors is gradually increasing in quality for some years. We are witnessing a generational change. I see 4-6 young filmmakers who are ready to debut, and I think that this trend is going to continue. The level of film education and professionalization of film schools, not only in Łódź but also in Katowice, Gdynia and Warsaw, is rising.

Central European Affairs: Have recent successes at the Oscars returned Polish cinema to its glory days of previous decades?

T.K.: Definitely. I think our position with festivals and the Oscars is stronger than it was a few years ago. I feel that the most upbeat aspect I can think of is the diversity of the films that enter into competitions at major festivals like Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Toronto, Tribeca, Busan, and others. Unlike some other nations who had their moments in recent years, such as films from Greece or Romania where you could observe a somewhat similar approach towards form, Polish cinema is very diverse. I see it as a very big advantage.

Touching on similar themes as our discussion with Kolankiewicz, we turn to Katarzyna Grynienko, a film journalist who predominantly writes with Film New Europe. Based in Warsaw, Film New Europe also has an office in Prague, and was founded by preeminent Polish director Andrej Wajda. Like Kolankiewicz, Grynienko is learned on world cinema, and similarly sends an optimistic message on the positive trends with the Polish film industry. She also eruditely recognizes that future imminent changes are still necessary as a result of this past year’s trying times. We posed very similar questions to Grynienko as we asked Kolankiewicz.

Central European Affairs: How have you surveyed the current film market, film festivals, and overall film distribution in the past year?

Katarzyna Grynienko: Film New Europe is always monitoring the market with a special focus on what’s going on in Central-Eastern Europe, as this region tends to get very little coverage with the international media. We succeeded to deliver our readers updates on each development when it comes to the different markets in each country with support from our local correspondents’ team, and with cooperation of the public institutions.

The exact box office numbers have been harder to track because of this quickly growing diversification caused by the pandemic. Several long awaited, major projects premiered on Video-on-Demand or Subscription Video-on-Demand much sooner than they would have if cinemas were opened. This has changed the box office and distribution landscape immensely. We have yet to see how permanent these changes are.

Central European Affairs: Even with an increase in online film fests, do you sense the whole paradigm has shifted indefinitely? What’s the blueprint like for all affected artists, critics, and film fest organizers?

K.G.: I feel that this situation will force festival organizers to host virtual events as “a second chapter” to the live event. The film industry community will celebrate the moment when live events will open again. Online festivals will not replace the real thing, but thanks to developing these online platforms, festivals can develop and maybe even double their audience. There will be one audience for those who sit in the cinema seats and others watching at home online.

Krakow Film Festival was the first online festival held in Poland and organizers hailed it both as a major interest, and as a major success, resulting in the establishment of a permanent online platform. In early February, the New Horizons Festival launched its VOD platform. This has shown that major festivals are capitalizing on the know-how that the period of the pandemic enabled them to implement. So, this is a positive thing.

Photo credit: Music Box Films

Central European Affairs: What are the main lessons do you feel Polish directors, cinematographers, actors, and other film personnel have learned during these months? How specifically has period adversely affected their careers?

K.G.: I think production crews were forced to minimize the scope of their work, and this might have introduced new, efficient solutions. A big trend in our region has also been the construction of ecological film sets. I know that this trend thrived during the pandemic.

Central European Affairs: In general, what do you make of the current crop of film artists from Poland in recent years? Any new crop of talents you look forward to on the horizon?

K.G.: This might sound very patriotic of me but Polish cinema has been on a steady rise for the last couple of years. Ever since ‘Ida’ by Paweł Pawlikowski won an Oscar for Best Foreign Film, Polish cinematography has also been even more noticed by those in the international arena.

I think I would mention Paweł Maślona, Piotr Domalewski, Kuba Czekaj, Magnus von Horn and Agnieszka Smoczyńska. They all propose a very individual outlook on modern Poland. Their works transcend the local market, and were appreciated by international audiences.

Cover photo: “Ida” by Paweł Pawlikowski – Photo credit: TIFF

Jared Feldschreiber is a freelance reporter and contributor to Central European Affairs Magazine. He is based in Warsaw, Poland, and often chronicles literary figures, filmmakers, and dissidents in nascent democracies. Reckless Abandon, his novella, is available worldwide.

Twitter: @jmfeldschreiber

Photo credit: Ilan Sherman