In April 2021, to commemorate the 78th anniversary of the start of the Warsaw Jewish Ghetto Uprising, a monument was unveiled in the heart of the Polish capital that consisted of a glass cube above an underground chamber. This great touchstone in Warsaw had been a long-forsaken Holocaust-era archive that was hidden by Polish Jewish volunteers. The Ringelblum Archive, named after the leading historian and teacher, Emanuel Ringelblum, “gave new life to those who died and the testimony of those who witnessed the horrors. It also provided insights into daily life by including rationing cards, medical prescriptions, theatre programs, and candy wrappers,’ as reported by Times of Israel. Roughly 30,000 documents were retrieved, and above all, the archive proved that Jewish lives not only lived in the ghetto but showed a tremendous zest for living, as well as persisting with great dignity against the German Nazis.

’What we know about Emanuel Ringelblum and his band of collaborators was that they were documenting the daily life of Warsaw’s ‘closed quarters,’”

Monika Krawczyk, the director of the Jewish Historical Institute tells CEA Magazine. “The whole situation of the Jews was slowly cooked to the extent that people from day one were not aware of what was happening. So, for Emanuel Ringelblum, as a social activist, and as an intellectual, [and] all those people who had worked for newspapers, schools, political parties, and social organizations, they were left without employment from one day to another.” As has often been the case throughout its arduous and long history, “Jewish organizations always tried to come together. The same thing happened from the first day of German occupation in Warsaw,” adds Krawczyk. “They came together and created a crisis committee, and then they created a social committee that was funded by the American Joint Committee. It was independent of the Jewish Council, which was the German-imposed administration of the Warsaw Jewish community [ghetto].”

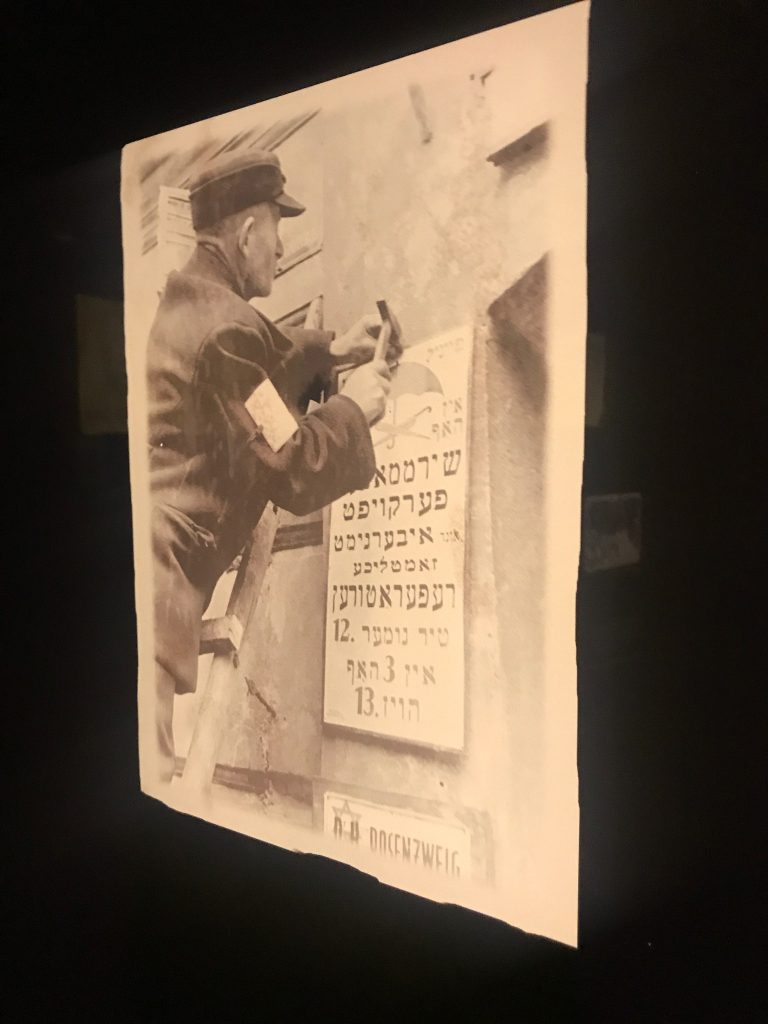

Severe laws were instituted within the Warsaw Ghetto that greatly restricted Jewish life though some businesses still persisted before its liquidation.

Photo Credit: Jared Feldschreiber

An attorney by profession, Monika Krawczyk served as the managing director of the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage between 2004-2019, and as recently as 2018, she also took part in the work of the Social Council at the POLIN Museum of the History of the Jews. Krawczyk was born in Olsztyn and since Jan.2021, has served as the director of the vaunted Jewish Historical Institute. This public cultural and research establishment, which was created in 1947, became the continuation of the Central Jewish Historical Commission. A remarkable center for learned inquiry, scholarship, and home for a vast array of collections of diaries and manuscripts, ghetto survivors had created it.

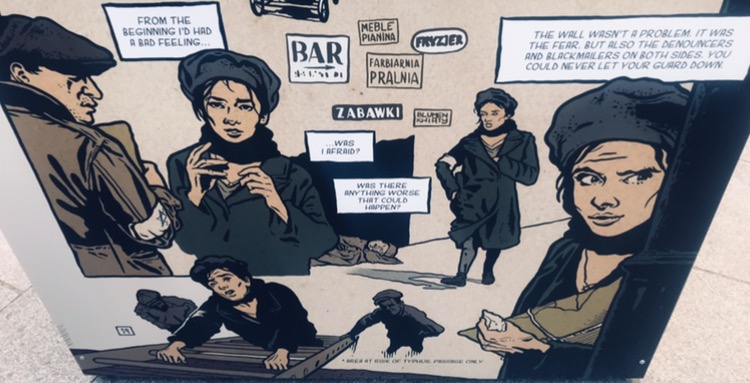

“The Ghetto is Burning” is a recent comic book publication by Polish illustrator Tomasz Bereznicki. It depicts the extraordinary sacrifice and personal bravery by Jews who lived in the Warsaw Ghetto. The comic book’s release was created to coincide with the 80 year anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. An exhibition at Plac Grzybowski in Warsaw is being presented until Dec. 2023.

Photo credit: Tomasz Bereznicki.

The third week of July 2023 marks the eighty-first anniversary of the start of the Murdered Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto, and to honor it, the Jewish Historical Institute – for its twelfth straight year – has planned a walk that is open to the Warsaw public. The March of Remembrance marks the painful recognition of twelve weeks between July 22 to Sept. 21, 1942, when German Nazis deported Jews living in the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka extermination camp. At that time, trains left regularly from the transshipment yard called the Umschlagplatz with overcrowded wagons of Jews sent to Treblinka. During this time, around 300,000 Jews were recorded to have been killed. According to the Jewish Historical Institute’s flyer, “The March of Remembrance will be accompanied by the outdoor exhibition, ‘Roots of Uprising. Resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto,’ which will present various circles of Jewish underground activists during the German occupation, their strategies, methods of operation, and the dynamics of cooperation. The story will revolve around the fate of several activists: representatives of various generations and political groups and environments.

Jews living in the squalid conditions of the Warsaw Ghetto often had to report their activities to the Judenrat (Jewish Council); an administrative body established in German-occupied Europe during WWII which purported to represent a Jewish community in dealings with the Nazis.

Photo credit: Jewish Archives, Poland

The main thrust of the Jewish Historical Institute stays paying homage to the price of human dignity that existed in the ghetto during the Nazi occupation. Mordechai Anielewicz, for instance, who was born in Wyszków, had been the principal leader of Jewish armed resistance against the Nazis. He was the focal figure in the Jewish Ghetto Uprising, which began on April 19, 1943. After first escaping to Vilna — now Vilnius, Lithuania — when the Nazis invaded, he eventually made his way back to the Warsaw ghetto, and set up the underground newspaper, נגד הזרם (“Against the Stream”), while he organized many cultural and educational activities. Ultimately, Anielewicz commanded the Jewish Fighting Organization known as Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB) in the spring of 1943. Sadly, when the Nazis found the ŻOB’s headquarters and bunker in early May, he along with one hundred others were gassed and killed. The ŻOB continued fighting valiantly without him but the Nazis quashed this uprising completely by May 16, 1943.

To coincide with this year’s events, the Ringelblum Archive will also have a coinciding exhibition in Munich, Germany at the Documentation Center of Nazi History. Entitled “More Important than Life: The Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto,” the exhibition displays around a dozen original items from its very archive, including sound recordings spoken by actors from Munich’s Kammerspiele theater. “The presentation in Munich is pretty much the same idea as what we have in the permanent exhibition here in Warsaw,” says Krawczyk. “Our purpose, firstly, is to promote the permanent exhibition that we have here because the story is so wonderful and interesting, but it’s not known. The other [aspect] is that we wanted to show it to the German public because they also should understand that the Holocaust, for which they are responsible, was not only that the killing was done in such vast numbers, but that there were specific lives and specific stories. We wanted to show what these people did, and that it was a form of resistance. It was not just taking for granted what was happening, but there was deep conscious activity to save human dignity. This is what we wanted to show the German public.”

On a sunny day in mid-July in Warsaw, one can reflect on the heroism of Anielewicz, Ringelblum, countless other Jewish lives, and ordinary Poles who did what was right. All of whom showed great resolve and human dignity in the face of unspeakable cruelty. One can also marvel that these battles were fought in these very streets and that the work of modern-day docents, scholars, and researchers, specifically at the Jewish Historical Institute, is doing a remarkable job of keeping this tragic history alive. “The Jewish Historical Institute on Tlomackie St., was [remarkable] as pre-war Tlomackie Square had many buildings and many [addresses],” concludes Krawczyk. “Out of that, only our building survived, and this library was built [in the fashion] of the synagogue, which was just next door.”

Jared Feldschreiber is a freelance reporter and contributor to Central European Affairs Magazine. He is based in Warsaw, Poland, and often chronicles literary figures, filmmakers, and dissidents in nascent democracies. Reckless Abandon, his novella, is available worldwide. Twitter: @jmfeldschreiber