CEA Talk podcast

„Bolsonaro would like to reach Orbán’s power level,” says Ariel Goldstein, sociologist and political scientist of the University of Buenos Aires. The Argentinian researcher was the first guest of the Civitas Talk podcast and discussed similarities and differences between the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Host: Balázs Csekő

There are similarities with Hungary when we take a look at how Bolsonaro came to power,” says the sociologist. A major corruption crisis including all the traditional parties – Workers’ Party (PT), Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) and the Social Democratic Party (PSDB) – shook the Latin American country and led to a remarkable distrust of the political class.

It was the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro who then saw his chance arrived and took advantage of the political crisis. With a political strategy and discourse based on polarization – he described his opponents as „leftist enemies” and „red thieves” – Bolsonaro could capitalize on strong feelings against the political elite. Bolsonaro, formerly a marginal politician with little support, was surprisingly elected President of Brazil in 2018.

Dilma’s mistake

The political distrust dates back to 2014 when the acting President Dilma Rousseff won the presidential election claiming to be a welfare state candidate and wanting to pump money in the economy and achieve economic growth.

“However, when she won the election, she did the opposite by appointing the orthodox Finance Minister Joaquim Levy, responsible for an economic shock,” tells Mr Goldstein. “The distrust was big after that and the popular sectors stopped their support for the Workers’ Party.”

“This situation had similarities with Hungary where corruption allegations appeared during the center-left governments mixed with an economic crisis,” the sociologist says.

Four pillars of Bolsonarismo

Mr Goldstein thinks Bolsonaro’s presidency could have hardly been a reality without the support of four key actors: agricultural sector, evangelical churches, financial markets and the military.

Bolsonaro secured the support of the agricultural sector by promising landowners to expel the members of the Landless Workers’ Movement from their land, if necessary by shots. Even the Democratic Union of Ruralists, a major right-wing farmer association endorsed Bolsonaro’s candidacy.

An especially important player are the evangelical churches. With the decline of the Catholic Church in Brasil, the evangelical pastors and their churches have started to expand across the country and play an important role.

Similar to Orbán, Bolsonaro has introduced a conservative agenda in gender issues. Slogans like “we are going to preserve the traditional family” and “we are going to defend the Christianity in Brasil” belong to his discourses and conservative people approve them.

Bolsonaro regularly assists to demonstrations organized by evangelicals inside and outside the temple. He was the first President to participate in the Jesus March, the most distinguished evangelical event in Brasil.

The evangelical groups have strong ties with Israel. They think of Israel as the promised land and defend the move of embassies from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem as part of the recognition of Israel as the land of salvation. Bolsonaro courted evangelical voters when he was baptized in the Jordan River by Pastor Everaldo Pereira, president of the conservative Social Christian Party.

In recent years the number of evangelicals has risen in the Brazilian Parliament where currently one-third of the deputies belong to the evangelical community – the most important block of support for Bolsonaro.

The financial markets are also on the President’s side. “The current finance minister has a very orthodox, pro-business vision of the economy,” claims the researcher. During the election campaign Bolsonaro linked the Workers’ Party to Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela, saying that another “PT government” would establish “a corrupt socialist government, destroy the country and produce misery and hunger similar to Venezuela.”

In Mr Goldstein’s view, another key sector to Bolsonaro’s administration is the military. “The support of the leading military figures was key to his election victory and they are the most important supporters of his government.”

The myth

Bolsonaro, whose nickname is “o mito”, isn’t simply seen as a ‘myth’. His followers call him that way, because they consider him to be “someone exceptional who is going to produce a salvation in Brasil,” explains the sociologist.

“His followers don’t judge him from a rational perspective, just follow him like a myth who cannot be question and criticized.”

He presents himself as a charismatic figure who has a divine mission. He presents himself as a hero.” The recovery from the knife attack he suffered in Minas Gerais during the 2018 election campaign strengthened his image as “someone rescued by god”.

“It’s a very effective form of politics,” says Mr Goldstein. “We see this also in the US with Trump.” Politicians like Bolsonaro and Trump don’t exercise government on the basis of transparency or rational presentation of arguments. “They expect obedience from their followers in a form that doesn’t coexist with criticism, debate or pluralism,” he states.

Leaders like Bolsonaro have conflicts with scientists because they present themselves to be above science, rational discussion or debate. They don’t admit critics and demand obedience. The ghost of authoritarianism is very present.

The role of Brazilian media

The researcher says the media made a “mistake for democracy” during the 2018 presidential election when it presented both Jair Bolsonaro and his opponent Fernando Haddad (Worker’s Party) “equally dangerous” for democracy.

Mr Goldstein acknowledges the phenomena of corruption during 15 years of Workers’ Party government, but says that “they were respectful for democracy”. The mainstream media, he claims, presented a party that governed with pluralism and transparency for more than a decade just as hazardous as the “authoritarian danger” of Bolsonaro. “I don’t think that was objective”, he says.

Another error committed by the media, Mr Goldstein claims, is that any leftist reform that the Workers’ Party tried to achieve was presented as “chavismo”, a reference to Venezuela’s former President. Bolsonaro didn’t invent this kind of discourse, but he capitalized on it. “Brazilian media offers different opinions but it should criticize its own role.”

Bolsonaro and Orbán

According to the sociologist Bolsonaro “is much weaker than Orbán.” The Hungarian Prime Minister rewrote his country’s constitution, had the opportunity to apply censorship on the media and expel the CEU from Hungary.

Bolsonaro hasn’t had the capability yet to do similar things due to different factors. First of all, he still has not consolidated a major support in society for such changes. Also the Brazilian media is strong with O Globo having the largest audience. “It’s very difficult to undermine and establish censorship to O Globo,” the researcher says.

But Bolsonaro could have long-term plans. In 2019, at the Brazilian embassy in the US he said openly that a “lot of things have to be destroyed before making a big change. It’s a long road.”

Whether he will have time for major reforms, still remains to be seen. Mr Goldstein is not sure Bolsonaro will get another mandate as Brazil’s leader and whether he has the capability to consolidate an authoritarian regime like Orbán. One thing is for sure, “Bolsonaro would like to reach Orbán’s power level”.

Possible solution?

The researcher advocates for revealing the characteristics of the populist leadership representing “danger for democracy” to a wider public.

“We have to re-establish the rational public discussion to confront this kind of authoritarian and irrational leadership,” he adds. The goal should be to expand the message so that the citizens are more conscious of the dangers for democracy.

“These regimes could be very dangerous for humans, because we live in pluralism and we grow in the diversity of exchange of ideas,” Mr Goldstein says. “These regimes tend to defeat one of the most valuable characteristics of humans,” he concludes.

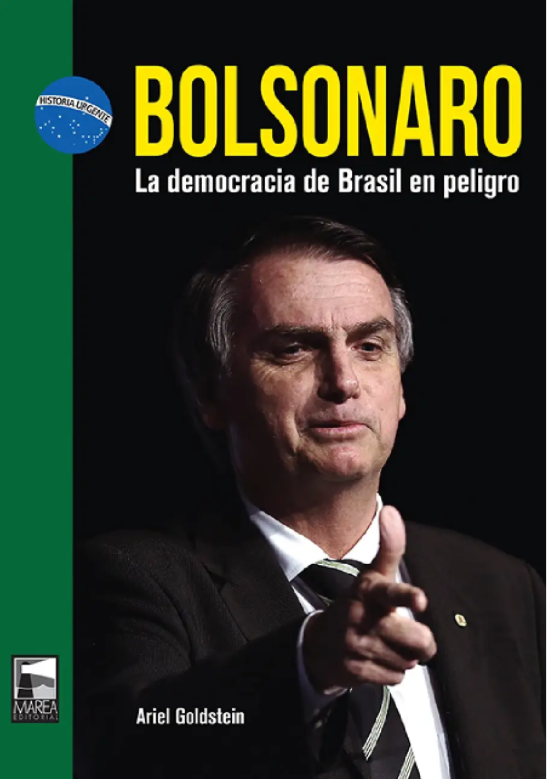

Cover photo credit: Rovena Rosa, Agência Brasil

Ariel Goldstein is a sociologist, political scientist and researcher of the Institute of Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the University of Buenos Aires. He has published plenty of articles in academic journals in the US, Spain, China, Brazil, Argentina and other Latin American countries. He is a specialist in the areas of media and politics in Latin America, with special focus on Brazil and Argentina. He is the author of several books, including “Bolsonaro: Brasilian democracy in danger” (2019) and “Evangelical power: How religious groups are taking over politics in America” (2020). Twitter: @AGoldok

Photo: Ariel Goldstein