Dr. Katarzyna Person, the deputy director of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum that is set to open in 2026, has been awarded the Dan David Prize. Headquartered at Tel Aviv University and established in 2001, recipients of the prestigious honor “reward innovative and interdisciplinary work that contributes to humanity.” Dr. Person’s focused commitment to Holocaust studies as a professor, researcher, and writer on a number of books and articles, as well as editing volumes of many documents from the Underground Archive, has collectively earned her much respect as a renowned scholar.

Author: Jared Feldschreiber

In addition to her tenure at the Institut für Zeitgeschichte, where Dr. Person worked on a project exploring relations between Polish and Jewish Displaced Persons in postwar Germany, she also held fellowships at Yad Vashem, the Center for Jewish History in New York, and the Institute of Contemporary History in Munich. The crux of Dr. Person’s research rests with her attempts to answer how atrocities are remembered and “who and why society chooses to silence them,” as reported earlier this month by YnetNews.

Dr. Person, who received her doctorate from the University of London, graciously answered questions prepared by CEA Magazine’s Jared Feldschreiber in an anxious time for Jews as they reaffirm their robust identity and rich lineage while confronting the scourge of rampant anti-Semitism worldwide.

CEA: As deputy director of the soon-to-open Warsaw Ghetto Museum, what will be your primary duties? Briefly comment on what visitors can expect to learn while there.

Dr. Person: The planned opening of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum is in 2026. The museum is based in the historic Bersohn and Bauman Children’s Hospital. It’s an institution that served the pre-war Warsaw Jewish community and then served as a hospital in the Warsaw Ghetto. This building of immense historical importance is one of the few surviving buildings from the Warsaw Ghetto. It’s currently being adapted and transformed into a museum that will tell the story of Jews in Warsaw from the late 19th century until the end of World War II, with a focus on the history of the Warsaw Ghetto. It is a huge undertaking, and by preparing the exhibition, we’re attempting to tell the stories of life and suffering during the Holocaust in all their complexity. An important aspect of our work is locating documents and artifacts linked to the Holocaust in Poland, and in particular, the Warsaw Ghetto, which can help us tell this story.

CEA: What were your duties as head of the Research Department of the Jewish Historical Institute?

Dr. Person: I had the privilege of working there for many years, firstly on its exhibition and then the publication of documents from the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto. This was the Ringelblum Archive. It was a unique opportunity to engage with texts that were created during the Holocaust, an experience that undoubtedly shaped me as a historian.

CEA: You have just mentioned the Ringelblum Archive, which is also an essential touchstone of your research. Please give a primer on it and how it’s a cornerstone to best understanding the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

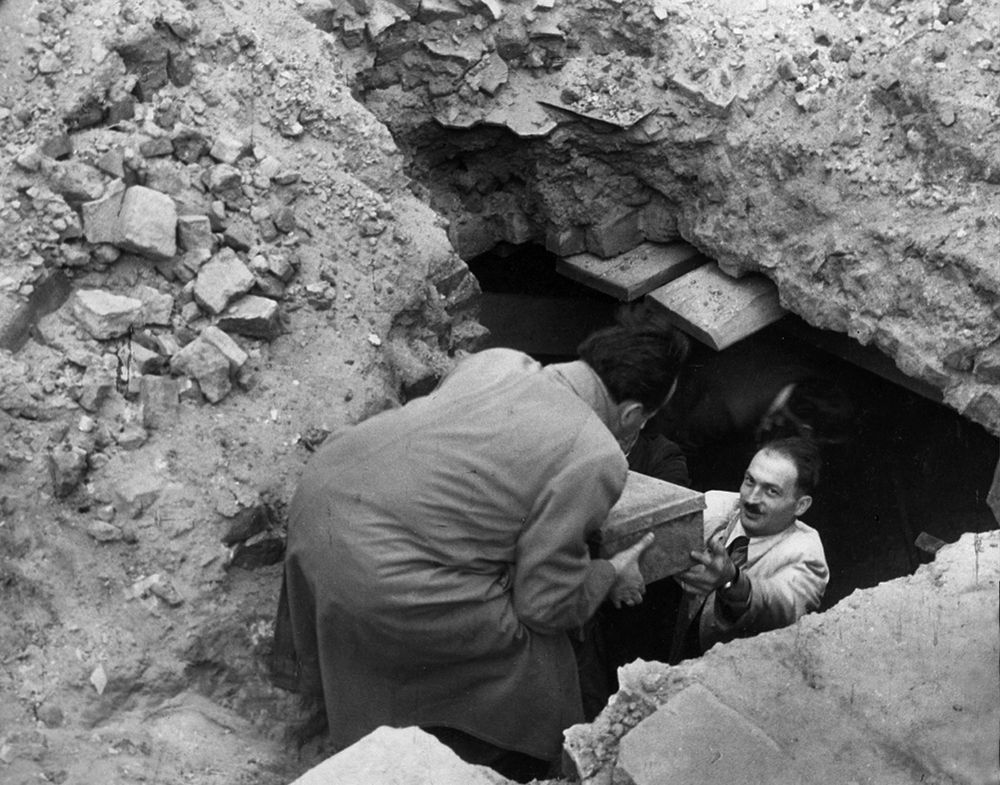

Dr. Person: The Ringelblum Archive was a clandestine archive functioning in the Warsaw Ghetto from late 1940 until early 1943. It was set up by historian Emanuel Ringelblum to document, as completely as possible, the fate of Polish Jews during the Holocaust. It aimed to achieve this by collecting an immense variety of sources, from postcards, diaries, posters, official German documents, school essays, and interviews to poetry, songs, and dramatic works. The aim of the archive was to capture the complexity of the ghetto experience through capturing voices that otherwise would have been erased: those of women, children, the elderly, deportees, and refugees, but also those of the ghetto elite, rabbis, intellectuals, or members of the ghetto administration. The archive was hidden in the ghetto and uncovered shortly after the war. It remains one of the most important sources for the history of the Holocaust as experienced by its victims.

CEA: What makes the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April ’43 a singular moment in the annals of Jewish and European history?

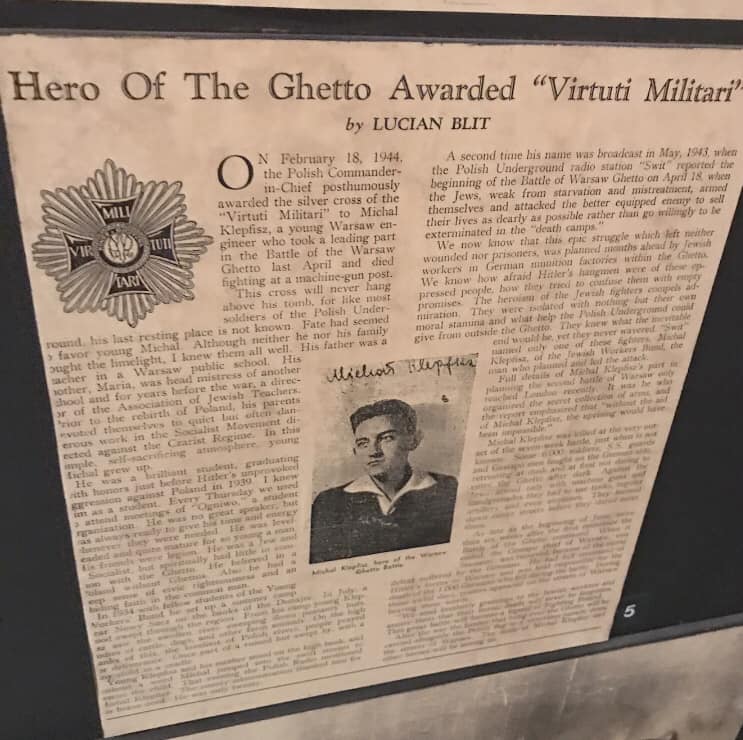

Dr. Person: The 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the first urban uprising in occupied Europe and the largest single act of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. It was a revolt of young people with basic training and almost no weapons who nonetheless stood up against German units entering the Ghetto. During events commemorating the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, we remember not only their sacrifice but also the fate of civilians who, during the uprising, perished in hideouts in the burning ghetto and were murdered on its streets or in the Treblinka death camp.

The commemoration of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19 and the march through the streets of the former ghetto on the anniversary of the beginning of deportation action from the Warsaw Ghetto on July 22 are the two key public events bringing back the memory of the victims of the Warsaw Ghetto into the space of today’s city.

CEA: Briefly tell us about your time as a leading Holocaust scholar and how your work continues to tackle a vast array of Holocaust-related subjects. How did you settle on your particular focus?

Dr. Person: I began with a PhD on assimilated Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto, which I defended at the University of London. This topic naturally led me to further research on voices, which, for many reasons, were not part of the main narrative of the Holocaust. I worked in particular on the stories of women, and those after the war were rejected by other survivors as “collaborators.”

CEA: One of your books delves into the “Image of the Jewish Order Service” in the Warsaw Ghetto. What psychologically could have led some Polish Jews to opt to join the police ranks with the Nazis? Was their thinking calculus about survival, betrayal, or naïveté that “things would ultimately work out in the end?”

Dr. Person: My main takeaway from this work is that the key to understanding the Jewish wartime leadership, both official and unofficial, is to appreciate the diversity of attitudes and their individual motivations, as well as the influence of wartime realities. One must consider the brutality of everyday life under occupation and the blurring of acceptable behavioral boundaries. Their actions were taken through a complex calculation of the benefits and losses that individuals thought they could decipher at the time, before the full consequences of their actions could be known.

CEA: What does achieving the Dan David Prize for your work on “Holocaust archives and the recovery of marginalized voices” mean to you as a historian, as a woman, and as a Pole?

Dr. Person: This is a very important prize and, of course, one that will significantly facilitate my future research, especially as my current project deals with the experience of life and death in small ghettos in villages and small towns in occupied Poland. It requires research from a vast number of archives and archival sources.

CEA: With the number of Shoah survivors dwindling, what do you consider to be three overarching pieces of wisdom and historical insight you can impart to the Jewish diaspora on the essential and urgent need for Holocaust education?

Dr. Person: We all must listen to the voices of those who were killed during the Holocaust and those who survived it. While the survivors are increasingly no longer with us, many voices were preserved in vast oral history documentation projects, as well as in memoirs, diaries, testimonies, and wartime collections such as the Ringelblum Archive. It is of key importance to make these collections as accessible as possible and, if necessary, translate them so we can all learn from them. It is also very important, while of course difficult, to go back to the physical spaces where the Holocaust happened—camps, cities, towns, and villages.

By being in those spaces and talking there about the victims, we both learn and commemorate them, even if for one moment, bringing back their memory into spaces from which they were often erased.

Cover Photo Credit: Luigi Ventimiglia Photography

Jared Feldschreiber is a freelance reporter and contributor to Central European Affairs Magazine. He is based in Washington D.C., and often chronicles literary figures, filmmakers, and dissidents in nascent democracies. Reckless Abandon, his novella, is available worldwide.

Twitter: @jmfeldschreiber

Photo credit: Ilan Sherman