The first time I went to Moldova it was by accident. Spending my summer vacation with some friends in Romania, we planned to visit the Eastern part of the country – Moldavia. While English, and my native Hungarian, make a clear distinction between Moldova and Moldavia, the Romanian language does not. Both are Moldova – the region, and the country, too. That’s how I ended up in Moldova instead of Moldavia after a two-hour-long wait at the Sculeni border crossing, the main entry point to the Republic of Moldova from Romania.

Author: Szabolcs Szalay

The first surprising thing was that in the brand new EU-financed terminal all the police officers were surprisingly young people in their 20s. The second thing that shocked me that none of my Belgian and Hungarian bankcards worked at the petrol station where we stopped. Not a typical thing in Europe, but I had to get used to it for the time I spent in Moldova. That first day for me was the best illustration of the position Moldova is in – putting the EU flags on new infrastructure, but lacking a deeper European connection. But the big picture is: as if time has stood still. This country that might be the best place in Europe for those who love melancholy.

Often dubbed as the poorest state of Europe, Moldova held a referendum, together with its presidential elections, on the further alliance with the European Union. The result, even if praised by Ursula von der Leyen, is rather a big question mark than a confident victory, and clearly shows the shortcomings of the “European dream.”

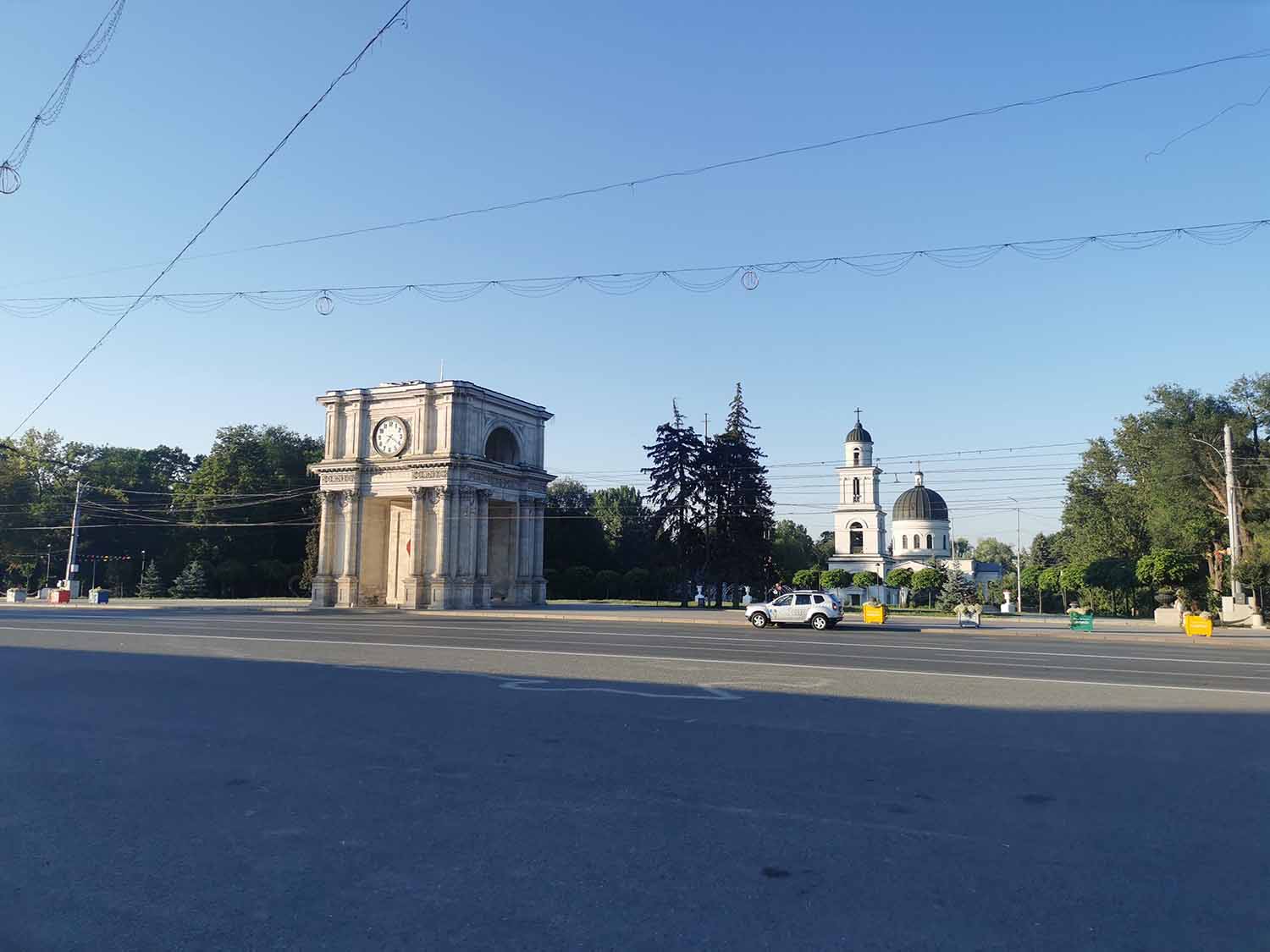

It would be hard to call Moldova’s latest three decades a success story. The small country, stuck between the frontier of the East and the West immediately faced serious ethnic conflicts at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union. After a short war, the Eastern – and more industrialized – part of the country seceded. Even though lacking international recognition, the so-called Transnistrian Republic is still a state within the state with pro-Russian leadership, mixed Russian, Ukrainian and Romanian-speaking population and with confusing relationship to official Moldova. The other autonomous region of Moldova, Gagauzia, home of a tiny Turkish-speaking but Orthodox Christian nation, has never broken away from the control of Chişinau, but with its pro-Russian sentiments, is trying to actively block any Moldovan attempt to build closer relations with the European Union. Although the “rest” of Moldova is often seen as a Romanian-speaking area from Europe, the reality is somewhat different. Walking on the streets of the capital city, Chişinau, Russian is as often heard as Romanian – that is still called Moldovan in the constitution and considered to be a separate language by a part of the local population.

Russian connections are still strong. It is not hard to find people in Moldova with very positive feelings about Russia and having nice memories of the times they lived there, even if the number of Moldovans living and working in the Western countries might vastly outnumber those who have chosen Russia as their second home – especially since getting a Romanian passport, and thus free access to the EU labor market is an easy and popular process throughout the country. The result is shocking: according to the official data the country with originally somewhat less than 3 million people has lost 450 thousand inhabitants in the past ten years. The, frankly, too young police officers I saw on the border crossing might be there because their more experienced colleagues have possibly left.

Referendum on EU membership?

The question that was put on the voting ballots of the referendum seems to be a perfect product of symbolic politics. “Do you support the amendment of the Constitution with a view to the accession of the Republic of Moldova to the European Union?” the government asked Moldovan citizens without giving any further indications about what exactly should be amended in the constitution and even if this modifications will be done, how and when will it result in an EU membership for the country. Nothing unheard of, politics is an art full of symbolism. Especially if an openly pro-European candidate is clashing with openly pro-Russian candidates on the presidential elections held on the same day.

Yet, what the pro-European incumbent president Maia Sandu might have believed to be a perfect asset to highlight popular support for her policies and gain legitimacy to step further, turned out to be a two-edged sword. While Sandu won the presidential elections, she has to face a pro-Russian candidate in the second round due to the low turnout. The referendum has left an even bigger question mark about the future of Moldova.

The evening of the vote turned dramatic for those who expected a strong pro-European result. For several hours nays were even leading, and only after the counting of the votes abroad could the referendum succeed. With 50.4 percent of the yes, besides a turnout of 51 percent. However some of those who were talking about serious breaches a couple of hours earlies, started to see the referendum as a big victory over Russia, and even the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen considered the result to be the sign of an independent and strong Moldova that wants a European future, the EU would seriously deceive itself by not paying attention to the low margin, the low voters’ turnout and Russia’s possible interference as well as the results coming from the Gagauz region.

Deep gaps, lacking answers

As Europeans, of course, we can only be happy if a nation shows a clear will to join our community and to accept our values. It would be a very positive outcome if President Sandu could secure a victory in the next round of the elections, and indeed manage to anchor European future in the Moldovan constitution, as she promised. But still, there is no real reason for exaggerated optimism.

The low turnout still shows that Moldovan people do not have much trust in democratic institutions and the small margin is a clear sign of the deep dividing gaps in the society regarding the country’s path. The picture is not much brighter even if the high number of negative votes was the result of Russia’s interference: in this case we have to ask the question if it was something unexpected by the Moldovan authorities, or it was expected and yet, not much was done to avoid it, indicating how fragile the Moldovan democracy is. The electoral map at the same time shows serious divides between urban and rural areas, and especially between Gagauzia and the rest of the country: in the autonomous republic the refusal of the European future was almost complete. Issues that are needed to be addressed urgently if the European Union wants to keep Moldova on the Western track.

Driving from Iaşi, Romania, to the Moldovan capital it is hard not to see the fruits of the European support. A state-of-the-art border terminal, a Western-quality highway and modern trains – all with European flags and boards to remind everyone, where the funds were coming from. Yet, while having our breakfast in our Chişinau hotel’s dining room, right under a television airing Russian disco hits, we had to conclude with my friends that what worked more or less in Central Europe, does not seem to work that well in Moldova. Infrastructural investments can hardly cover the numerous problems Moldova has to face: the fact that the country is still lacking the ability to keep its population at home, the ethnic tensions, the unsolved issue of Transnistria, and the low level of trust in democracy.

It is time for the EU to acknowledge that only by spreading out money they will not be able to build the “European dream” further. A European dream that is not just serving people with the freedom of movement but also with reasons to stay in their native countries and perspectives for a better life there. A European dream that does not just guarantee elections in every four years, but also the accountability of institutions and politicians in the meantime. A Europe that is courageous enough to deal with ethnic minority issues. A Europe that is not just complaining about Russian interference but does everything in its capacity to maintain its independence from malicious foreign actors. The result of the referendum in Moldova was unfortunately not a glorious victory, but a wake-up call for Europe.

Cover photo credit: Szabolcs Szalay

Szabolcs Szalay is an international relations expert with experience in foreign policy advisory in the Hungarian National Assembly and the European Parliament.